Chapter 2 General Features of Psychological Tests

Psychological tests are commonly described as objective and standardised measures of a sample of behaviour (e.g. Anastasi & Urbina, 1997; Janda, 1998). A test is objective if its administration, scoring and interpretation are clearly specified and replicable. A test is standardised if these specifications are adhered to and uniformly applied. A standardised test often uses a large comparison group (i.e. norm group) for interpretation of test scores. A test is a sample of behaviour if its content or administration involves only some of the possible activities and/or some of the possible circumstances with which the test is concerned. For example, a test might be concerned with mathematical ability. The test may involve several mathematical problems to be solved without a calculator and with a time limit. This test will contain only a sample of the possible mathematical problems that could be included. Furthermore, it samples mathematical problem solving behaviour under quite specific circumstances i.e. without a calculator, with a time limit, and possibly in an anxiety provoking situation. Thus, quite apart from the specific content of the test, the testing situation itself should be viewed as a sample of all the possible circumstances where solving maths problems could be demonstrated. Tests, then, are concerned with samples of behaviour. However, the behaviour being sampled is often regarded as an indirect index or sign of some underlying concept such as ability (e.g. verbal, numerical, spatial) or personality (e.g. extraversion, agreeableness, etc). Such concepts have four features in common:

• They are concepts used to summarise and describe observed consistencies in behaviour. • These concepts are usually regarded as theoretical constructs that encompass more than the original set of observations. • There is no single set of questions or items that can be used to measure the construct. There must instead be a sampling of relevant questions/items from the universe of items within the construct domain. • The construct must always be related, either directly or indirectly, to observable behaviour or experience.

Tests that claim to measure intelligence are clearly sampling behaviour that is considered to be a sign of a broad theoretical concept. The same may be said of more narrow measurements such as mathematical ability, or even tests that attempt to measure the concept of ‘knowledge’ of a subject area. However, it should be clear that the aspiration of tests to measure broad constructs must always be limited by the fact that they involve only a sample of behaviour which may not be representative.

There can be some tests that are narrow enough in their concern that they are often regarded as directly sampling the almost complete behaviour e.g. a typing test, spot welding test and other ‘work’ samples where there is a ‘point-to-point’ correspondence between behaviours assessed through the sample and some of the behaviours required within the job. Of course, there is still problem that the circumstances of testing may be unrepresentative.

2.1 Types of Psychological Test

Psychological tests can be broadly categorised according to the type of construct they claim to measure:

Intelligence tests: One of the oldest types of psychological test is the ‘intelligence’ test which claims to measure overall basic reasoning ability. Modern versions of these tests include the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS- IV), the Stanford-Binet test (for ages 4-17) and the British Ability Scales (for ages 2 ½ -17 ½). These three tests have to be administered on an individual basis. Other intelligence tests can be administered to groups e.g. Raven’s Progressive Matrices, The Culture Fair Tests, and the Alice Heim 3 (AH3).

Specific Ability tests: The above intelligence tests measure very general ability, other types of test are designed to assess more specific ability factors, the most important of which are considered to be verbal ability, spatial ability and mathematical reasoning (Kline, 2000). For example, the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal measures verbal reasoning and is used within graduate recruitment and management selection. Sub-scales within general intelligence tests may also be considered as tests of specific ability e.g. the arithmetic scale of the WAIS. There are also a number of tests that assess very specific factors e.g. the Purdue Pegboard (a measure of finger, hand and arm dexterity).

Aptitude tests: Occasionally, the above specific ability measures are referred to as aptitude tests. However, it is more usual for the term ‘aptitude test’ to be used when the test contains a mixture of underlying abilities needed for a particular course, job role or occupation (e.g. General Clerical Test, Computer aptitude test).

Achievement (or attainment) tests: The above ability and aptitude tests often claim to measure the potential for learning or acquiring a new skill, in that they aim to assess necessary underlying abilities. In contrast, achievement tests measure the level of knowledge or skill attained by an individual through instruction (e.g. university examinations).

Interest tests and Values tests: Typically tests of interest contain a large number of items about whether various activities, situations and types of people are liked or disliked e.g. the Vocational Interest Measure (VIM), The Strong-Campbell Interest Inventory (SCII). Tests of values attempt to measure a person’s basic philosophy and orientation to the world e.g. The Study of Values, the Rokeach Value Survey.

Personality tests: these usually contain a large number of items about feelings and behaviour and attempt to measure fundamental differences in temperament e.g. The Californian Psychological Inventory (CPI), the Myers-Briggs Type indicator (MBTI), The 16 Personality Factors Test (16PF), Quintax.

Integrity tests: These tests attempt to identify potentially counterproductive or dishonest employees. Some of these tests may be described as overt tests in that they ask directly about dishonest activities and attitudes towards dishonesty e.g. the London House Personnel Selection Inventory; the Reid Report. Other integrity tests may be described as covert tests in that they aim to measure aspects of personality related to counterproductive behaviour, such as unreliability and carelessness e.g. Giotto

2.1.1 Specific Features of each Type of Test

2.1.1.1 Tests of Maximal Performance

Tests of intelligence, specific ability, aptitude and achievement (for which items have a correct answer) are often described as tests of maximal performance (how well a person can do). Such tests most commonly consist of multiple-choice items. Here, an item presents a problem to be solved (termed the stem), followed by a choice of possible answers (typically around five and termed the response set) only one of which is correct (termed the keyed response). The incorrect answers are termed distracters. These tests of maximal performance can be classified as either Power tests, speed tests or speeded tests:

Power tests have no time limit, or a limit that is long enough so that about 90% of test takers can attempt all items. Such tests usually have items that gradually increase in difficulty so that, for most people, a limit in the ability to solve the problems is reached.

Speed tests have a time limit that prevents all items from being attempted, but which if given without a time limit would be correctly solved by most people. Here it is speed of response that limits performance.

Speeded tests will fall somewhere between the two extremes above. There is a time limit that affects the number of items correctly solved and the tests have some difficulty, often gradually increasing difficulty.

Tests of maximal performance can be further classified as either norm-referenced or criterion-referenced. With norm-referenced tests, a person’s score (how many items were responded to correctly) is compared with others (known as a norm group) to establish a relative position. With criterion-referenced tests, the concern is with a standard of performance, the presence or absence of a certain level of skill, knowledge or achievement. Such use, sometimes known as mastery testing, involves classification (e.g. pass or fail) or diagnosis (identification of what action needs to be taken).

With tests of maximal performance, the behaviour being sampled often appears quite directly related to the construct e.g. the measurement of spatial ability may involve the mental rotation of three-dimensional drawings.

2.1.1.2 Tests of Typical Performance: Normative and Ipsative

Tests of personality, interest and integrity (for which there are no ‘correct’ answers) are often described as tests of typical performance (what the person typically does). Such tests commonly consist of items that ask questions about behaviour, beliefs or feelings (e.g. Do you listen carefully when talking with others?), to which a yes /no response is required. Alternatively, the items are statements (e.g. I am often impatient to make my point during conversations), to which either a true/false response is required, or there is a rating scale with 5, 7 or 9 points. Rating scales require an indication of the extent to which the statement is true of the respondent, or the strength of agreement with the statement. Most tests of typical performance measure more than one construct, so that a number of items may be concerned with, for example, conscientiousness, other items may be concerned with openness to ideas, and so on. Regardless of whether the test measures just one construct or many, the response formats so far described allow respondents a free choice of agreeing or not agreeing with each question or statement. Such ‘free choice’ formats are sometimes termed normative measures.

A few tests of typical performance contain items that present a forced choice between statements. Here, an item contains more than one statement and there is a requirement to indicate which is most true. Alternatively, there is a requirement to rank order the statements from most to least true. Below is an example showing just two items from a forced choice test:

Please indicate which of the following statements is most true of you.

- Question 1

- I am almost always on time for appointments

- I am very intrigued by new ideas

- Question 2

- Once started I usually finish a task

- I have varied interests

Note that each item above requires a choice involving more than one construct. The first statement within each item above appears to be concerned with conscientiousness and the second statement appears to be concerned with openness to ideas. Thus, when completing a forced choice measure with many such items, the greater the number of statements that are endorsed for any one construct within the items (e.g. conscientiousness), then the lower must be the number of statements endorsed for the other construct within the items (e.g. openness to ideas). Because of this, it is not possible to score very highly or very lowly on all constructs within forced choice measures. In fact, because every item receives a score, either for one construct or another, the total of scores over all constructs measured will be the same for all respondents; it will just be the distribution of scores between the constructs that will differ. This forced-choice format is sometimes used to reduce socially desirable responding, as with the above example, where both options within an item appear to be equally desirable.

Forced-choice measures are sometimes termed ipsative measures. From the above description, their two key features may be summarised as:

• The options within each item of the test require choices involving more than one construct • The total score over the constructs being measured will sum to a constant number for all individuals

Good ipsative measures are difficult to construct. Also, because a total score is shared out between the constructs, such tests are better suited to measuring the relative strengths of preferences within individuals rather than absolute strengths between individuals (for which normative measures are best suited). With tests of typical performance the behaviour being sampled can appear quite indirectly related to the construct i.e. the behaviour here is responding to statements and questions, perhaps accurately, through the judgement of one’s feelings, behaviours, attitudes, etc.

2.2 Using Tests for Occupational Purposes

The main uses for tests within occupational settings may be categorised as:

• Part of the selection process for entering an organisation or for promotion within an organisation • Aids for team building, managing change and other organisational issues • Aids to personal development or career guidance

Whatever the particular use for the tests, there should always be a clear focus on the assessment needs, and a concern with good practice. The British Psychological Society (the BPS) has a Code of

2.2.1 Good Practice for Psychological Testing

http://www.psychtesting.org.uk/the-ptc/guidelinesandinformation.cfm This code outlines what is expected by the BPS when using tests, and includes:

Responsibility for Competence e.g. ensuring that test users meet all the standards of competence and endeavour to develop/enhance this competence.

Appropriate Procedures and Techniques e.g. ensuring that the test is appropriate for its intended purpose. Storing test materials securely, and ensuring that no unqualified person has access to them. Keeping test results securely, and in a form suitable for developing norms, validation and monitoring bias.

Client Welfare e.g. obtaining informed consent of potential test takers, making sure that they understand what tests will be used, what will be done with their results and who will have access to them. Ensuring that test takers are well informed and well prepared for the test session. Providing the test taker and other authorised persons with feedback about the results. The feedback should make clear the implications of the results, and be in a style appropriate to the reader’s/hearer’s level of understanding. Due consideration should be given to factors such as gender, ethnicity, age, disability and specific needs, educational background and level of ability in using and interpreting the results of tests.

The particular details for good practice will be derived from the particular purpose for testing. For example, a code of practice for Careers Guidance might include:

• The starting point will always be the particular needs of the individual client.

• The service provider should be aware of the competencies required within different occupations and endeavour to assess the level of fit between applicant and job, which may include tests of interest, style, motivation and ability

• Service providers will be trained to meet the British Psychological Society (BPS) standards for occupational testing

• Test users will monitor the extent to which the tests are fair for all

• No client will be given an inappropriate or unnecessary test

• All clients will have the right to confidential feedback

• The client has ownership of the test results and no copies should be kept without prior consent

• All materials should be kept securely and with access only by appropriately trained users.

2.3 The Usefulness of Tests in Selection for Jobs

Ability tests and personality questionnaires are widely used within employee selection. An older survey by Hodgkinson and Payne (1998) revealed the popularity of these methods for graduate selection is not new (see Table 2.1).

| Selection.method | UK | Netherlands | France |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Interviews | 90 | 85 | 45 |

| Situational interviews | 15 | 29 | 23 |

| References | 77 | 24 | 19 |

| Ability tests | 49 | 22 | 27 |

| Personality tests | 41 | 22 | 26 |

| Biodata | 10 | 16 | 5 |

| Assessment centres | 26 | 15 | 0 |

| Application forms | 83 | 66 | 55 |

| Graphology | N/A | 0 | 9 |

A more recent survey by Zibarras and Woods (2010) revealed the higher use of structured interviews along with ability/aptitiude tests in larger organisations.

Importantly, good tests offer reliable and valid measurement. The specific meanings of these two terms will be explored in detail later. For now, we shall describe reliability as consistent measurement and validity as meaningful measurement.

One aspect of the meaningfulness of measurement is the extent to which a measure (or score) is related to external criteria (i.e. criterion-related validity) Within occupational testing, this criterion may be job performance. There will of course be many ways of measuring this criterion and thus many potential ways of establishing criterion-related validity.

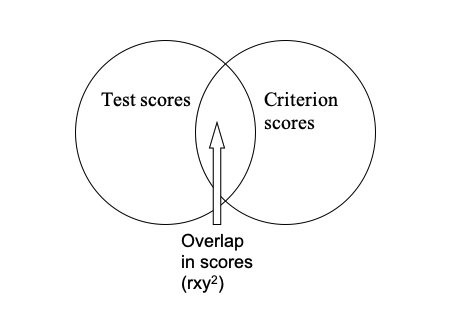

Criterion-related validity is established through obtaining a set of test scores from a large group of people and then obtaining some measure of criterion performance for these same people (e.g. job performance scores). The two sets of scores can then be correlated to give what is known as a criterion-related validity coefficient. Since these validity coefficients are correlation coefficients, their values will range from 0 to 1.00, and are usually symbolised as rxy i.e. the correlation (r) between test scores (x) and criterion scores (y).

Table 2 overleaf shows reported criterion-related validity coefficients for a number of selection methods, including general mental ability (GMA), for job performance (from a classic 1998 meta-analysis).

| Personnel.measures | Validity.rxy. | Multiple.R | Gain.in.validity.from.adding.supplement | X..increase.in.Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMA tests | 0.56 | NA | NA | |

| Integrity tests | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.11 | 20% |

| Conscientiousness tests | 0.30 | 0.65 | 0.09 | 16% |

| Employment interviews (all types) | 0.35 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 5% |

| Peer ratings | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 1% |

| Reference checks | 0.23 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 9% |

| Job experience (years) | 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0% |

| Biographical data | 0.30 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0% |

| Years of education | 0.20 | 0.60 | 0.04 | 7% |

| Interests | 0.18 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 5% |

A similar table (table 3 below) may be constructed showing the criterion-related validity of methods for training performance.

| Personnel.measures | Validity.rxy. | Multiple.R | Gain.in.validity.from.adding.supplement | X..increase.in.Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMA tests | 0.56 | NA | NA | |

| Integrity tests | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.11 | 20% |

| Conscientiousness tests | 0.30 | 0.65 | 0.09 | 16% |

| Employment interviews (all types) | 0.35 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 5% |

| Peer ratings | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 1% |

| Reference checks | 0.23 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 9% |

| Job experience (years) | 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0% |

| Biographical data | 0.30 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0% |

| Years of education | 0.20 | 0.60 | 0.04 | 7% |

| Interests | 0.18 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 5% |

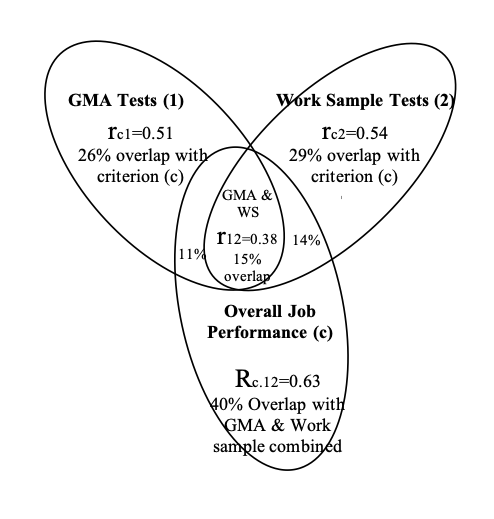

The validity coefficient (r_{xy}) for GMA given in table 2 is from an analysis involving over 32,000 employees in 515 diverse jobs (Hunter, 1980; Hunter and Hunter, 1984). This value of 0.51 is actually for ‘medium complexity’ jobs within the sample. Schmidt and Hunter (1998) state that this level of complexity includes 62% of all the jobs in the US economy. This level of job includes ‘skilled blue collar’ jobs and ‘mid-level white collar jobs’ such as upper level clerical and lower level administrative jobs. Within this diversity of ‘medium complexity’ jobs there was reported to be little variation around this value of 0.51. This analysis goes on to report that where validity coefficients did differ, this was for very different levels of job (see Table 2.4). Again, within each broad level of job there was reported to be little variation in validity coefficient.

| Job.Level | Validity.Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Professional managerial | 0.58 |

| High-level complex-technical | 0.56 |

| Medium complexity | 0.51 |

| Semi-skilled | 0.40 |

| Completely unskilled | 0.23 |

This analysis suggests that GMA test validity is generally high. Furthermore, the analysis revealed little variation in the validity of ability tests within very broad job families, and thus tests may be said to have considerable validity generalization.

The above U.S. work has been supported by more recent European meta-analyses (e.g. Bertua, Anderson & Salgado, 2005; Salgado, Anderson, Moscoso, Silvia, de Fruyt & Rolland, 2003). Salgado et al (2003) report validity for GMA measures across 12 occupational categories in the European Community. They report large validities for job performance and training success in 11 of these categories. Here again, job complexity (low, medium or high) moderated the size of these coefficients. The authors report that these findings are similar to those found in the U.S., although the European data revealed slightly higher validity coefficients in some cases.

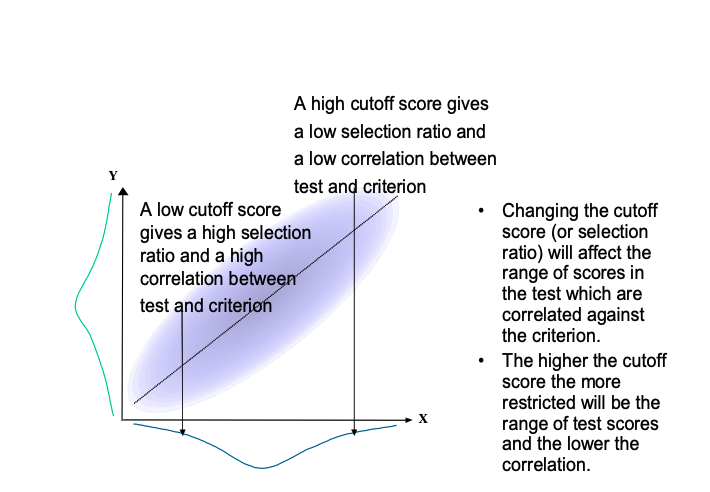

2.4 Validity Generalization and Meta-analysis

The above picture of generally high and stable validity coefficients is quite different from the general view of ability tests held until the late 1970s. Then, it was generally believed that the criterion-related validity of ability tests was both generally low (i.e. around 0.3) and situationally specific. That is, the validity for a given type of test seemed to be quite different for slightly different job roles and even different locations. However, most of the studies, and especially early studies, used small sample sizes. Because of the small sample sizes involved in any one study, any single study may slightly overestimate or underestimate the ‘real’ relationship between tests and criterion. This is a type of sampling error, which can give rise to seemingly situationally specific validity coefficients. Combining the results of these smaller studies allows the researcher take account of this sampling error and evaluate the extent to which there are real differences between coefficients across job roles and locations. This was the method used by Schmidt and Hunter above which found little ‘real’ variation in coefficients within very broad job families. This method of combining many small studies is termed ’meta-analysis’ and allows for an evaluation of validity generalization. Meta-analysis is often termed validity generalization within psychological testing. Often validity generalization results are also ‘statistically adjusted’ so as to take account of the reliability of the criterion measurement. Low reliability in criterion measurement will lower any correlation between test and criterion. Validity generalization techniques also take account of differences between job applicants and job incumbents. This is because criterion-related coefficients can only be calculated once people are performing the job. Thus, if the test was used within selection, then the coefficient calculated will not include the whole range of test scores that were found within the applicants. This, in turn, will lead to an underestimation of the ‘real’ relationship between test scores and future job performance. See Figure 2.1 for an illustration of this effect.

Figure 2.1: An Illustration of the effect of changing the range of test scores on the correlation between test scores and criterion

The technique of validity generalisation can upwardly adjust the observed validity coefficients so as to allow for the restricted range of scores found within job incumbents compared to job applicants. This adjustment was used by Schmidt and Hunter to construct the previous tables of validity coefficients and, as we have seen, this gives rise to quite high ability test validity. Cook (1998) suggests that these corrections give ‘estimated mean true validity’ of about twice the mean uncorrected validity.

2.5 Implications from Validity Generalization

The technique of validity generalization has revealed that similar tests have quite stable validities for very broad job families. Thus, test users can have some confidence that if a test has evidence of validity for a particular job role, then there is likely to be validity with similar tests in similar job roles. Thus it may be reasonable to assume that test validity information obtained in one situation may generalize to similar situations. Nevertheless, when generalizing from specific validity information, one should check that:

• The conditions of the original validity study are similar to the conditions to which one wishes to generalise. For example, a test for the selection of supervisors in an industry with mostly male employees may not show the same validity when used to select supervisors for more mixed industries.

• The criterion is similar (e.g. rate of product production may be quite different to supervisor ratings).

• The original validation sample size is adequate.

• There is a check for restricted range on both test and criterion within the original validation study.

• Differential prediction has been considered (i.e. validities may differ for different groups of people).

2.6 Determinants of Job Performance

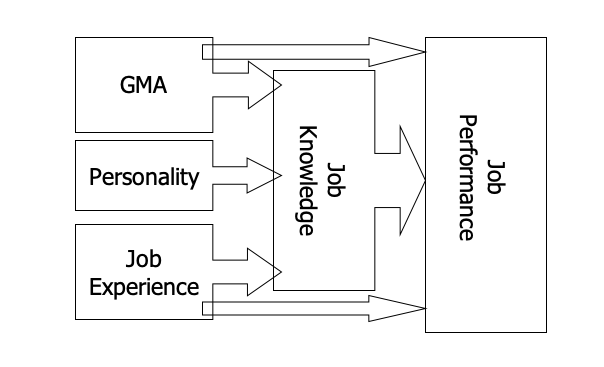

According to Schmidt and Hunter (1992), mental ability has a direct causal impact on the acquisition of job knowledge which in turn leads to higher job performance. They claim that mental ability also has a smaller direct effect upon job performance. These authors also state that job experience, up to about 5 years, operates in the same way, with the major effect of job experience being on job knowledge. Finally, they claim that personality, in particular conscientiousness, also influences job knowledge and thus job performance.

Figure 2.2: An Illustration of the suggested relationships between Job Performance and its Determinants (constructed from Schmidt & Hunter, 1992)

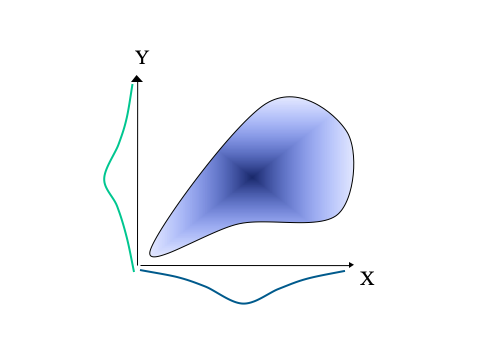

The model in Figure 2.2 gives an important role to job experience, up to the first 5 years. Schmidt, Hunter and Outerbridge (1986) report that when experience does not exceed 5 years, the correlation between experience and job performance is around 0.4. These authors report that after 5 years the correlation becomes increasingly weak, with further increases in job experience leading to little improvement in job performance. Thus, as shown previously in table 2 (p.10), the overall validity of job experience for predicting job performance is only 0.18. Table 2 was based on a meta-analysis that included a wide variety of experience, from less than 6 months to more than 30 years. This pattern of relationship, where there is initially a rather strong linear relationship between the predictor and criterion, which then breaks down at the higher end of predictor scores, is termed a twisted pear relationship (Fisher, 1959). Such a relationship is quite common within psychometrics and is illustrated in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3: Figure 3: An illustration of a twisted pear relationship. Scores on the criterion (Y) and the predictor (X) are quite strongly correlated at the lower end of predictor scores, but there is no correlation at the higher end of predictor scores.

2.7 What is meant by General Mental Ability (GMA)

General mental ability is thought to underlie performance on a whole range of ability tests. Spearman (1927) argued that differences in general mental ability are a result of differences in three basic mental processes: the apprehension of experience, the eduction of relations and the eduction of correlates. As an example, consider the simple problem presented below: Ankle is to foot as wrist is to?

To solve this analogy, there must first be a perception and understanding of the terms based on past experience (apprehension of experience). Secondly, there must be an inferring of the relationship between the terms (eduction of relationships). Thirdly, there must be an inferring of the missing term so as to satisfy the same relationship (eduction of correlates). For Spearman, then, general mental ability is, in short, the ability to ‘figure things out’. Though this may not seem to give much insight into the meaning of mental ability, this description would satisfy many people currently involved in the field of ability measurement.

2.10 Indicative General References on Selection

Beier, M.E., & Oswald, F.L. (2012) Is cognitive ability a liability? A critique and future research agenda on skilled performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 18, 4, 331-345.

Bertua, C., Anderson, N. & Salgado, J.F. (2005). The Predictive Validity of Cognitive Ability Tests: A UK Meta-Analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 387-409.

Bozionelos, N. (2005). When the inferior candidate is offered the job: The selection interview as a political and power game. Human Relations,58(12),1605–1631.

Christian, M. S., Edwards, B. D., & Bradley, J. C. (2010). Situational judgment tests: Constructs assessed and a meta-analysis of their criterion-related validities. Personnel Psychology, 63(1), 83–117. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2009.01163.x/full

Cook, M. (2009). Personnel Selection: Adding Value through People (5th ed). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Cortina, J. M., Goldstein, N. B., Payne, S. C., Davison, H. K., & Gilliland, S. W. (2000). The incremental validity of interview scores over and above cognitive ability and conscientiousness scores. Personnel Psychology, 53(2), 325–351. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2000.tb00204.x/abstract

Hough, L.M. & Oswald, F.L. (2000). Personnel Selection: Looking Toward the Future – Remembering the Past. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 631-664.

Krause, D.E., Kersting, M., Heggestad, E.D. & Thornton III, G.C. (2006). Incremental Validity of Assessment Center Ratings Over Cognitive Ability Tests: A Study at the Executive Management Level. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 14, 360-371. Kuncel, N.R. & Hezlett, S.A. (2010) Fact and Fiction in Cognitive Ability Testing for Admissions and Hiring Decisions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19, 6, 339-345 http://intl-cdp.sagepub.com/content/19/6/339.full

Kuncel, N.R., Ones, D.S., & Sackett, P.R. (2010). Individual differences as predictors of work, educational, and broad life outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 4, 331-336. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0191886910001765

Lievens, F., & Patterson, F. (2011). The validity and incremental validity of knowledge tests, low-fidelity simulations, and high-fidelity simulations for predicting job performance in advanced-level high-stakes selection. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 927–940. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023496

Macan, T. (2009). The employment interview: A review of current studies and directions for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 19(3), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.03.006

Piotrowski, C. & Armstrong, T. (2006). Current Recruitment and Selection Practices: A National Survey of Fortune 1000 Firms. North American Journal of Psychology, 8, 489-496.

Ployhart, R.E. (2006). Staffing in the 21st Century: New Challenges and Strategic Opportunities. Journal of Management, 32(6), 868-897.

Robertson, I.T. & Smith, M. (2001). Personnel Selection. Journal of Occupational and Occupational Psychology, 74, 441-472.

Rothstein, M. G., & Goffin, R. D. (2006). The use of personality measures in personnel selection: What does current research support? Human Resource Management Review, 16(2), 155–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2006.03.004

Ryan, A. M., & Ployhart, R. E. (2014). A Century of Selection. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1), 693–717. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115134

Sackett, P.R., & Lievens, F. (2008). Personnel selection. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 419-50. http://www.numerons.in/files/documents/Personnel-Selection-Paul-R.-Sackett-and-Filip-Lievens.pdf

Salgado, J.F., Anderson, N., Moscoso, S., Silvia, B.C., de Fruyt, F. & Rolland, J.P. (2003). A Meta-Analytic Study of General Mental Ability Validity for Different Occupations in the European Community. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 1068-1081.

Salgado, J. F. (2016). A Theoretical Model of Psychometric Effects of Faking on Assessment Procedures: Empirical findings and implications for personality at work. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 24(3), 209–228. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijsa.12142/full

Schmitt, N. (2014). Personality and Cognitive Ability as Predictors of Effective Performance at Work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091255

Schmidt, F. (2006). The Orphan Area for Meta-Analysis: Personnel Selection Retrieved October 30, 2016, from http://www.siop.org/tip/Oct06/05schmidt.aspx

Schmidt, F.L. & Hunter, J.E. (1998). The Validity and Utility of Selection Methods in Personnel Psychology: Practical and Theoretical Implications of 85 Years of Research Findings. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 262-274.

Schmidt, F.L. & Hunter, J.E. (2004). General Mental Ability in the World of Work: Occupational Attainment and Job Performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86,162-173.

Scior, K., Bradley, C. E., Potts, H. W. W., Woolf, K., & de C Williams, A. C. (2014). What predicts performance during clinical psychology training? British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 194–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12035

Scroggins, W. A., Thomas, S. L., & Morris, J. A. (2008). Psychological testing in personnel selection, part II: The refinement of methods and standards in employee selection. Public Personnel Management, 37(2), 185–198. Retrieved from http://ppm.sagepub.com/content/37/2/185.short

Scroggins, W. A., Thomas, S. L., & Morris, J. A. (2009). Psychological testing in personnel selection, part III: The resurgence of personality testing. Public Personnel Management, 38(1), 67–77. Retrieved from http://ppm.sagepub.com/content/38/1/67.short

Smith, M. & Smith, P. (2005). Testing People at Work: Competencies in Psychometric Testing. Oxford: BPS Blackwell.

Zibarras, L.D., & Woods, S.A. (2010). A Survey of UK Selection Practices Across Different Organization Sizes and Industry Sectors. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 499-511.